Communications for All – Part I

A strategy for democratic, popular control of our internet, phone systems, platforms and data

High prices. Dismal customer service. Poor network coverage. Tiny data caps. Huge overage charges. Dishonest marketing. Confusing contracts. Canadians are well acquainted with the rage-inducing dysfunctions of our telecommunications sector.

The architects of this system are a handful of corporate behemoths that control virtually all of our communications infrastructure. The Big Five – Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw and Quebecor – have perfected the art of squeezing ever-greater profits out of Canada’s captive market of mobile phone and internet users. In 2017, the profits of Canada’s “big five” telecommunications providers totalled $7.49 billion, and their profit margins have reached an astonishing 46.2 per cent.

Wielding their control over the nation’s cables and signal towers, the Big Five shut out smaller companies and keep prices high. They delay the rollout of new technologies and seek to undermine net neutrality protections. They slash funding for local journalism and outsource jobs abroad despite record profits. They refuse to produce Canadian content without generous public subsidies, but wrap themselves in the flag when facing the prospect of foreign competition.

High-speed internet and mobile phone service are a necessity for work and life in the 21st century but the monopolization of these essential services means that the rural-urban and rich-poor divisions are growing in Canada. Low-income Canadians struggle to pay for these essential services and are disproportionately shut out by the rising cost of connectivity. Those who live in rural and remote communities are forced to pay high prices for slow, unreliable service due to a lack of infrastructure investment.

There are proven, better ways to provide communications for everyone. In many European countries, affordable broadband internet and mobile phone service and even unlimited mobile data are a reality, thanks to stricter regulations and greater competition. In Helsinki, the local administration has created a free, city-wide WiFi network, offering speeds higher than in many other European capitals. In Chattanooga and other American cities, municipalities have created local broadband providers that provide faster speeds at a lower cost than the corporate ISPs. In Uruguay, the publicly-owned ANTEL has made the South American nation a world leader in fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) and wireless connectivity.

Even within Canada, the otherwise bleak telecoms landscape features a few bright spots. In Saskatchewan, SaskTel has proven that publicly-owned telecoms can help lower prices and ensure better service for rural customers without acting as a drag on the public treasury. And in many rural communities, municipalities are by-passing the corporate behemoths and setting up their own broadband service providers.

We can build a national, publicly-owned network that provides high-quality, affordable service to everyone. We can use the profits currently pocketed by shareholders to instead fund local culture and journalism in the public interest. And ultimately, we can protect our personal data from the prying eyes of spy agencies and Silicon Valley corporations and put “big data” to work for socially desirable ends.

To accomplish this, we propose four major steps towards a socialized telecommunications system:

CREATE ALTERNATIVES

Establish a national publicly-owned provider from the bottom up

The fight for a publicly-owned broadband and wireless infrastructure will be waged at many different levels, but it does not start from scratch. Existing public infrastructures and organizations, such as power companies at the municipal and provincial level and Canada Post, the CBC and even a repurposed Canada Infrastructure Bank at the federal level, will be key to creating a viable public sector challenge to the monopolistic Big Five. The struggle at all levels should carry a common demand: a federated and cooperatively managed telecommunications system in public hands. [Skip to this section]

BREAK THE POWER OF THE MONOPOLIES

Use regulatory powers to increase quality of services, end monopolistic practices and reduce prices

In the name of letting the “market” decide, our complacent, regulatory bodies captured by industry lobbyists have allowed the dominant telecom firms to build hugely profitable empires that make a mockery of any notion of public service. By enforcing existing regulations and enacting new ones, we can tilt the scales toward the common good, break up the vertically-integrated monoliths and give publicly-owned service providers the access to existing infrastructure they need to expand rapidly. [Skip to this section]

TAKE BACK CONTROL

Nationalize the telcos and implement cooperative federated control in the public interest

Years of privatization and deregulation have produced a telecommunications system that is a costly, inefficient, bureaucratic mess. Our ultimate goal must be an integrated, national network under democratic control, but this is impossible if we allow the present balkanized system of rival corporate fiefdoms to persist. Promoting alternatives is good, but on its own this strategy risks letting the ruling telecoms corporations hold on to the most profitable parts of the network while publicly-owned providers serve the most costly areas. By redirecting profits we can ensure equitable access to remote and low-income users, invest in improvements to service and fund community-controlled production of culture and journalism. [Skip to this section]

SEIZE THE FUTURE

Start building the data commons and take back the platform layer

Access to data has rapidly emerged as one of the most important economic drivers of the 21st century. Beyond privacy and control of data, we must create democratic alternatives to concentrated corporate control. If data is the future, we should control access, ensure privacy, and ultimately use it to improve delivery of public services and enhance democratic control of the economy instead of selling mass-scale behaviour manipulation to the highest bidder. In short, the data layer should be managed as a commons, and the power of public telecommunications should be used to shift social media and collaborative platforms away from corporate “walled gardens” and toward the kinds of open standards and federated services that made the internet so uniquely useful in the first place.[Skip to this section]

* * *

Abolish the digital divide; establish public alternatives

Internet connectivity is a vital part of everyday life in Canada. Increasingly, the internet is the medium of choice for staying in touch with friends, watching films, listening to music, searching for jobs, doing school work, accessing government services, paying bills, following the news and even waging political campaigns. Culture and entertainment, work and education, love and friendship, politics and business – our lives have become inextricably intertwined with the net.

The CRTC recognized this reality in a December 2016 ruling, declaring high-speed internet to be an “essential service.” But the CRTC’s ruling also acknowledged that high prices and a lack of infrastructure in remote and rural areas mean many groups of Canadian society find themselves unable to access this essential service. Low-income families, First Nations communities and rural and remote municipalities find themselves on the wrong side of a growing digital divide.

Stagnant working-class incomes are challenging enough. Combining them with the worst instincts of corporate telecom monopolies that raise the cost of broadband internet access and mobile phone service means many people now struggle to pay their telecom bills. For lower income households, internet and mobile phone bills account for nearly 5% of expenses, a bite out of the family budget that is two and a half times larger than for average income families. Millions of Canadians can’t afford to pay for broadband service unless they sacrifice other necessities, such as food, clothing, and healthcare.

Faced with such an excruciating choice, many poor and working-class Canadians are forced to do without internet connectivity entirely. Mobile phones and broadband internet are nearly ubiquitous in households earning over $82,000 per year (i.e. the top 40% of the population by income) but access to the internet is far less widespread for those in the bottom 40%. Nearly one-third (30.1%) of households in the poorest fifth of the population do not subscribe to a mobile wireless service, while nearly one-fifth (19.7%) of those in the second lowest fifth stand in the same position. Consequently, Canada ranks a lowly 24th out of 35 OECD countries in terms of mobile phone adoption. Internet access at home is similarly class-skewed, with 35.6% of the lowest income quintile and 17.9% of the second lowest quintile lacking a connection at home.

In Northern or rural areas, internet users pay even higher prices for slower and less reliable connections. Over 2.4 million Canadians (almost equivalent to all of Metro Toronto, or the entire Greater Vancouver area) cannot access the broadband speeds deemed essential by the CRTC at any price, for lack of adequate infrastructure. First Nations communities “are the most disadvantaged communities in almost all respects,” the CRTC notes.

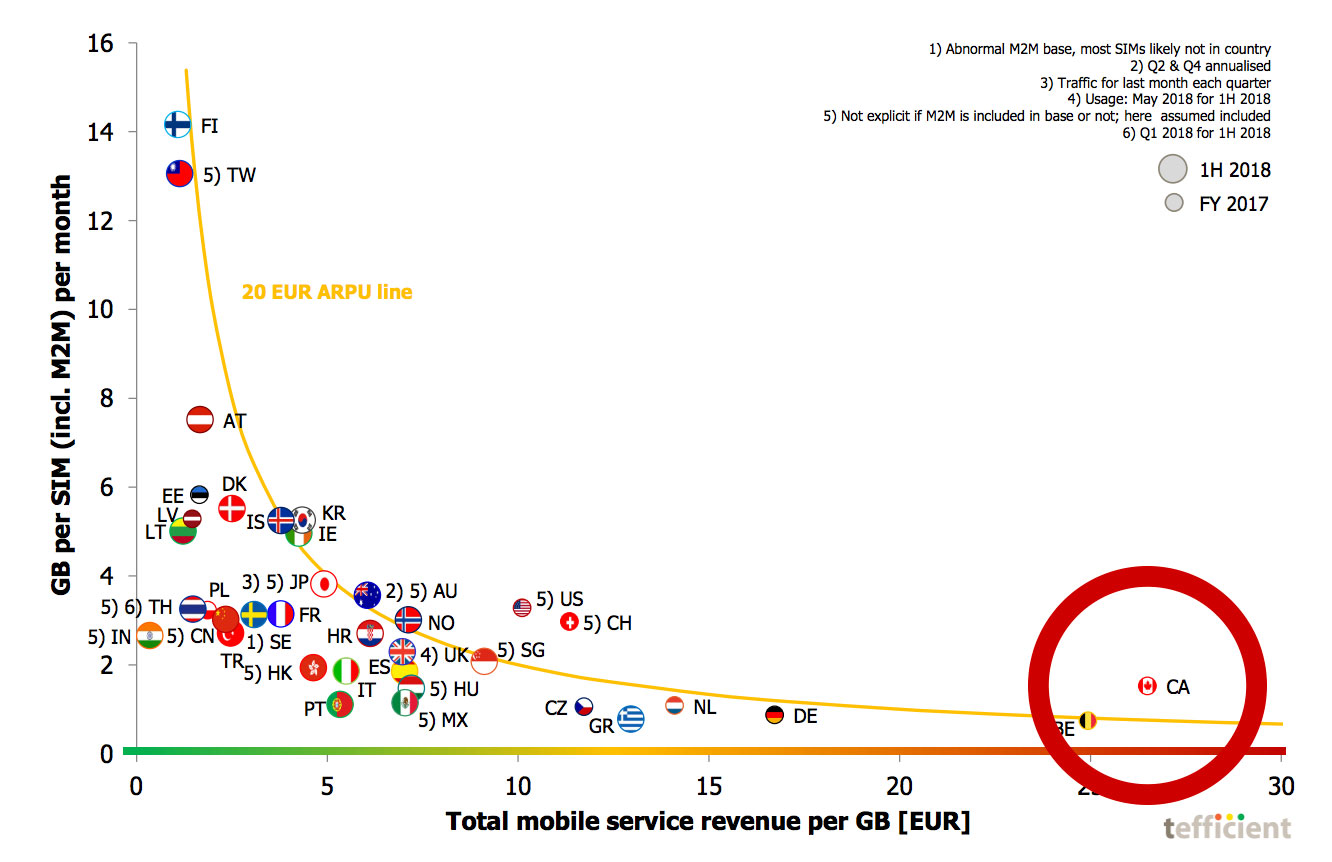

Internet users may be suffering from high prices, poor coverage and shoddy customer service, but Canadian telecom companies are doing great. In fact, they’re among the most profitable in the world. The telecommunications sector’s operating profits are consistently two and a half times higher than those of other non-financial industries, according to StatsCan. In a 2008 analysis by Merrill Lynch, the Canadian wireless market was the most profitable of the 23 countries surveyed. Seven years later, the investment bank repeated its analysis and found that the situation in 2015 was much the same. The Canadian wireless industry profit margin of 46.2 per cent was bested only by Portugal’s 47 per cent. In the bottom-ranked U.K., by contrast, telecoms could only expect a margin of 24 per cent. It’s easy to squeeze out robust profits when you don’t think about quality for remote users or providing affordable options for half the population.

Establishing publicly-owned broadband ISPs and wireless carriers – mandated to provide low-cost, high-quality services to all Canadians – is a crucial first step to abolishing the digital divide. The task of forging an inclusive, democratic and cooperative telecommunications system is daunting, but we are not starting from scratch. The key is to piggyback on already-existing public infrastructure and institutions, such as municipally- and provincially-owned power companies. Many municipalities have already connected public buildings with fibre optic cables, whose unused capacity (known as “dark fibre”) could serve as the basis for an alternative network infrastructure.

Consider one bold, homegrown idea: communications scholar Dwayne Winseck has outlined a radical proposal for building a public telecoms challenge to the existing oligopoly at the federal level. Winseck proposes the merger of Canada Post and the CBC to create the Canadian Communication Corporation (CCC) with a mandate to become the fourth national mobile wireless provider. “The CCC,” Winseck declares, “could be to the broadband internet and mobile-wireless centric world of the 21st century what the Post Office was to the print world of times past.” The CCC would blanket cities with open access networks, develop public WiFi, mobilize the “vast stock” of under- or unused municipal fibre optic cables, and extend broadband internet access to people in rural, remote and poor urban areas. It would also fund public art and culture directly rather than through “an opaque labyrinth of intra- and inter-industry funds overseen by a fragmented cultural policy bureaucracy.”

The CCC could repurpose some of the CBC’s existing spectrum holdings and broadcast towers for mobile wireless service coast-to-coast-to-coast, real estate could be combined and used to site towers, local post offices used to sign up cellphone subscribers and sell devices, and Canada Post vehicles given more windshield time making sure that the country’s system of correspondence, communication and parcel delivery run as they should.

In a similar vein, CUPW has argued that Canada Post should get involved in broadband internet services and suggested that the federal government could “use Canada Post as a way of building the backbone of a new high speed network.” To begin the process, the union called on Canada Post management to create a Broadband Digital Strategy committee comprised of management, unions, Internet advocacy experts and representatives from other postal systems which already offer Internet services. Postal workers fighting privatization, linked up with journalists threatened by newsroom cutbacks could make a politically potent constituency behind a radical proposal like Winseck’s.

A guiding principle should be that infrastructure built with public funds should remain in public hands, instead of padding the bottom line of the already-profitable telecommunications giants. Currently, federal and provincial governments support the extension of telecommunications infrastructure to remote and rural areas through special funds and subsidies. This effectively lets the corporations off the hook for the cost of connecting more sparsely populated (and thus less profitable) regions while allowing them to keep the infrastructure once it is built. The Canada Infrastructure Bank, repurposed to support public enterprise instead of its current mandate of privatization, could also play an important part in financing the rollout and expansion of public telecoms infrastructure.

We are not obliged to wait for political change at the federal level to implement public alternatives. A fascinating example of what can be done through municipal broadband initiatives comes from an unlikely place: Chattanooga, Tennessee. A mid-sized, declining industrial town in the south with a population of 170,000, Chattanooga began its transformation into a pioneer of municipal broadband in 2007. That year, the Electricity Power Board (EPB, the city’s power company) decided install a “smart grid,” overlaying the power grid with fibre optic cables that track customers’ usage, allocate electricity more efficiently and help reduce outages. In the process, the EPB created a communications network that spanned the whole city and was many times more advanced than what was currently on offer. Confronted with the neglect of the area’s telecoms infrastructure by the dominant ISPs (Comcast and AT&T), the EPB decided to offer high-speed residential internet connections directly to the population via its fibre network.

Almost overnight, Chattanooga’s power company became the leading ISP in the city. The EPB has signed up 84,000 internet subscribers, representing more than half of the market share in the area, by offering connections with speeds many times faster and at half the price of its private sector competitors. The EPB also gives discounts to low-income residents and is a source of revenue for the city. Its ultra-high speed internet has attracted various startups to the town, creating a mini tech boom. The competition has forced Comcast and AT&T to upgrade their networks in the area and lower their prices.

Spurred by Chattanooga’s successes, over 450 towns and cities in underserved regions have jumped on the municipal broadband bandwagon. Socialist city councillor Kshama Sawant has called for Seattle to follow this path as well.

Multiplying Chattanooga-style municipal broadband initiatives in cities and towns throughout Canada is critical to challenging the duopolies that dominate broadband internet service at the local and regional level. Several Canadian municipalities have developed their own municipal broadband services. In Alberta, residents of the town of Olds have ultra-high speed internet thanks to a community-owned and -operated fibre optic network called O-Net. A one-gigabit connection from O-Net costs just $57 per month, while slower services in Calgary from Bell and Rogers cost between $115 and $226 per month.

It may be possible to apply the Chattanooga model on a much grander scale via provincially-owned power utilities. Hydro-Québec, for instance, has installed a similar fibre optic-based smart grid and since the early 2000s the public utility has studied the possibility of connecting clients in regions without access to high speed internet. Underserved municipalities have been demanding that the electricity company use some of its excess fibre capacity to connect them. And in the recent 2018 provincial elections, the left-wing party Québec Solidaire vowed to create a nationalized internet backbone provider, Réseau Québec, that would extend affordable fibre optic connections to rural areas in collaboration with internet cooperatives and other locally-owned ISPs.

Another interesting example of what can be done at the provincial level to challenge Canada’s telecoms oligopoly comes from Saskatchewan. The Big Three claim that high prices for mobile phone services are an inevitable consequence of our country’s immense geography and sparse population, rather than due to a lack of competition. This obfuscatory nonsense is spectacularly disproven by Saskatchewan, the province with the lowest population density – and the lowest rates for cellphone services. The province’s mobile phone users get lower prices and more data for their mobile phones than in other provinces because of the competition provided by SaskTel, the last provincially-owned telecoms company left standing in Canada after decades of privatization.

Wireless plans in Saskatchewan are $50 to $70 cheaper than their equivalents in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, thanks to SaskTel. Competition from SaskTel has forced the Big Three to lower rates for their Saskatchewan customers, by up to 40% for some plans relative to other provinces. In Regina, data-heavy plans are 26% cheaper than they are elsewhere in Canada. Prices are so low, in fact, that Canada now hosts a thriving black market of Ontarians clandestinely obtaining prairie mobile phone plans. And only SaskTel (along with MTS in Manitoba1) offers unlimited data plans. Even industry consultants hostile to the notion of a publicly-owned telecoms company admit that Saskatchewan has the best wireless rates in the country thanks to the “wild card” SaskTel.

SaskTel has enjoyed tremendous commercial success, taking a 67% share of the wireless market and regularly returning tens of millions of dollars in dividends to the provincial treasury. Endowed with a strong public service mandate, SaskTel has eschewed the abusive salesmanship of its rivals and invested heavily to ensure truly province-wide wireless coverage. While Bell, Rogers and Telus have limited their infrastructure spending to Regina and Saskatoon, SaskTel has built cell towers throughout the province. The crown corporation also boasts the lowest number of complaints per subscriber among wireless carriers, and year after year has won top marks for customer service from marketing firm J.D. Power. And contrary to the received wisdom that public enterprises are less innovative, SaskTel has been a leader among wireless carriers in upgrading its network and adopting the latest technological advances. It has accomplished all this while paying its CEO and board of directors one-tenth of what MTS (Manitoba’s privatized telco which is of similar size and was sold off in 1996) pays its corporate leadership. Taking SaskTel national, as UNIFOR’s David Coles proposed in 2014, could be an interesting way of challenging the hold of the Big Three over wireless.

To realize such latent possibilities will require a major political fight. Every step of the way, the EPB and the city of Chattanooga have faced intense lobbying and hostile media campaigns funded by the incumbent corporations. Tennessee state legislators have restricted the EPB’s expansion into underserved neighboring areas and imposed limits on the discounts the company can offer to low-income clients.

In Saskatchewan the current provincial administration is more interested in hobbling, rather than expanding, the crown corporation. To pave the way for its eventual privatization, Brad Wall’s conservative Saskatchewan Party government has sought to undermine SaskTel by cutting it off from new sources of revenue and limiting its activities outside of the province. Fortunately, the Wall government has been stymied up to now by the manifest unpopularity of such a move, even with the Saskatchewan Party’s own political base.

Continue reading Part II.

Main writer/researcher: Nikolas Barry-Shaw (with contributions from several Courage members)